Insanity in media has acted as the single most effective purveyor of understanding over the past centuries. The vast majority of this comes from fiction. It tends to be difficult to accurately portray something virtually incomprehensible to the neurotypical mind via logos. Therefore, we must resort to pathos. Luckily, several of the greatest works in fiction allow for empathy, the single most important factor in understanding. In the following, we shall explore a few of those, which were especially noteworthy for me.

Psychopathy is a very well-known mental illness. In fact, back in the 19th century, when Julius Ludwig August Koch popularised the term via his work by the name of Die Psychopathischen Minderwertigkeiten (The Psychopathic Inferiorities), he was referring to mental illnesses as a whole, rather than the much more specific definition today. When you think of insanity, psychopathy is often the first example that pops into your head. It is no surprise that media is riddled with psychopathic characters, from Othello to The Mask of Sanity. Psychopaths simply tend to make good stories, they allow for action, easy conflicts, established villains, etc. However, due to their popularity in fiction, they tend to be generalised and over-simplified (ie. any generic Marvel villain. Entertaining, but often shallow). Fortunately, there are a rare few, fairly popular, but still insightful psychopathic characters in great pieces of art, that allow us to actually understand psychopathy.

The Wasp Factory follows a young protagonist, Frank Cauldhame, with a peculiar father, estranged mother and an insane brother. This was Iain M. Banks’ first novel, in which he did not shy away from sharing his dark imagination. Frank is a deeply troubled individual, with a horrifically twisted worldview and psychopathic tendencies. Despite this, the issue of Frank’s insanity is never directly addressed in the book. Rather, it seeks to brush it aside, as if it were a meaningless accessory to Frank’s already complicated personality.

The Wasp Factory is somewhat of a successor to Crime and Punishment; where Crime and Punishment explores the mind of a killer, the Wasp Factory explores the mind of a psychopath. In both cases, empathy is key. It is difficult to make readers understand if they despise the character. Crime and Punishment does this via sympathy for Raskolnikov. The Wasp Factory simply introduces an even more insane character, in the form of Frank’s brother. How could Frank be insane, when his brother burns dogs, force feeds live maggots to children and is incarcerated in an asylum? Relatively, Frank is sane. Banks allows us to enter Frank’s mind, see how his grotesque decisions are made the same way as we might make our own daily decisions. There is no raving lunatic, convinced that something terrible would happen unless his cousins and brother died. There is no frothing at the mouth, just an impassive, calculating mind that came up with the depraved decision. They simply had to die just as one simply has to get rid of pests. This nonchalance is the key to letting the reader understand. For the reader to empathise, Frank cannot seem to be a psychopath. Sanity is in the eye of the beholder. And for just long enough, The Wasp Factory allows you to see through insane eyes.

The Wasp Factory itself is a large, emptied clock face with 12 passageways extending out of it, leading to different manners of death for captured wasps: fire, electricity, drowning, etc. Frank places a wasp into the clock face, after which it is locked into the inevitability of its own demise. Fate then proceeds to decide the manner of death. Frank likes this metaphor. He believes in the rigidity of fate, at least for the weak. His God complex forced him to believe that he is different, he rules his own fate, and he must carry out the fate of the weak. When he decides that his cousins and brother must die, it is only normal for him to carry out the inevitable task. He is the strong, the powerful, and it is his duty to be an agent of Fate.

Banks has a very matter-of-fact way of describing the murders, mixed in with a tinge of grotesque humour. Familial homicide is normal to Frank, and for a few moments, normal to the reader as well. Then, the reader zooms out, realises what has actually happened, but the job is done at this point. Banks has already made the reader understand and empathise with Frank. These scenes force the reader to reflect, how did such a grotesque scene feel so normal? Everything Frank does is rational if you ignore the part about him actually deciding that fate ordains the death of his cousins. It introduces the idea that insanity is simply one irrational decision made by an otherwise rational individual. One wrong step and you’re over the edge.

The Joker is perhaps the most famous exploration of the insane, broken mind. He is a masterpiece of fiction. The perfect blend of entertainment and meaning. A complex and multifaceted character, the Joker is well-known for his sudden outbursts of violence and destructive behaviour. Strangely though, his most terrifying moments are not those that involve maniacal laughter or senseless violence, but those that seem much more calm, calculated, controlled, perhaps even sane moments. After all, this is a monster. Pure evil. The very idea that someone like the Joker could seem normal is an affront to the pillars of civilisation. “How could the quintessential psychopath dare to resemble us, the sane?”, humanity cries incredulously. The mad are mad, the sane are sane, and the logic in you spits at the idea of an overlap.

There is much truth to this statement. If you remember the period around the release of the movie, critics and mainstream media published several negative articles around the movie, calling it uninspired, grotesque, nothing but violence. Several mass shootings preceded the release of the movie, and the media jumped at the chance to condemn the movie as an affront to the victims of violence. After all, the movie was rampant with anti-establishment themes and critiques of mainstream media. Once the movie was released however, it got stellar reviews from everyday moviegoers. Why? As with any magnum opus of fiction, the movie allows you to perceive something about reality, something that would make you understand the fractured mind that is the Joker, a momentary bit of empathy for the monster. And the thought that you are capable of comprehending that, that something is already inside you waiting for the “little push”, is the terrifying bit. Madness is not a different person, it’s you walking along a different path. The Joker is a visual representation of that path.

Schizophrenia may not be as well-known or represented as psychopathy, but it is one of the more intriguing forms of insanity. Schizophrenia has always seemed somewhat special and unique to me. Even Koch differentiated delusional insanity from psychopathy in Die psychopathischen Minderwertigkeiten, so perhaps people shared my view even in the Gilded age. Around the same time as Koch published his work on Psychopathic Inferiors, the term dementia praecox was introduced, which roughly translates to early dementia. It was thought of as an early deterioration of the brain. This term was gradually replaced by schizophrenia.

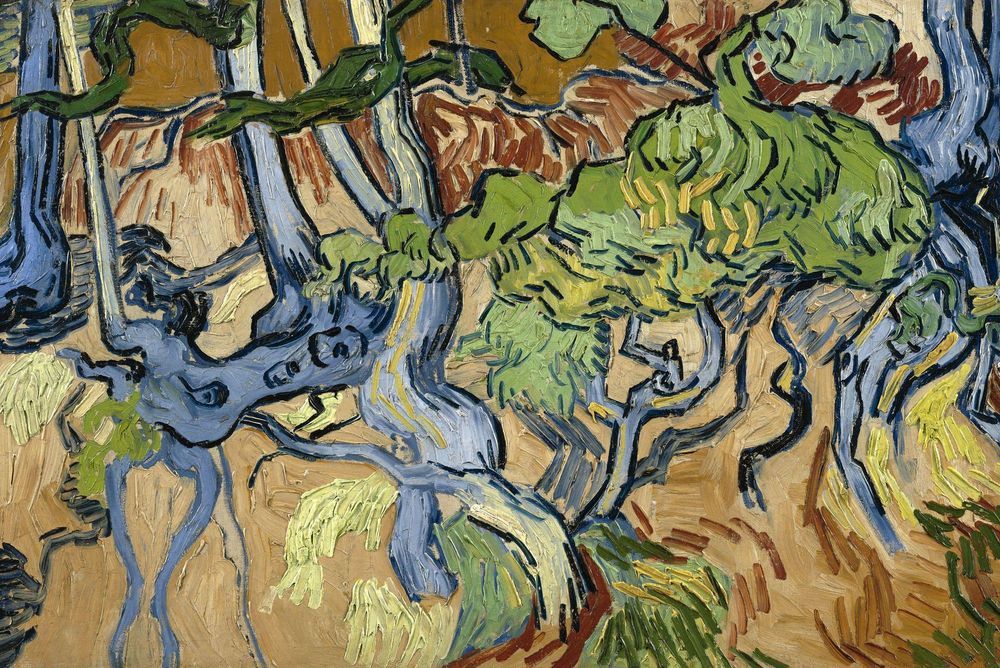

Schizophrenia, in simple terms, is one not knowing what is real and what is not. The idea of your own brain lying to you is quite interesting. Who can you trust, if not yourself? As Don Quixote undertakes his chivalrous quests, an observer is undoubtedly intrigued. The idea of reality not being real is confounding, to say the least. At the same time, it is a great mystery of how this would feel like. To look back upon the past and realise it was fake, how must that feel? Luckily, we have the imagination of great authors to show us. Don Quixote is Cervante’s tour de force, and an amazing piece of fiction, no doubt. But, Don Quixote’s imaginary monsters might scare away some readers. Or perhaps its age and length. Luckily, an author by the name of Neal Shusterman as written a much shorter, more modern, but just as insightful book by the name of Challenger Deep. Challenger deep is based on Neal’s own schizophrenic son, Brendan.

Challenger deep is a constant shuffle between the two lives of it’s protagonist, Caden Bosch. Of course, one is real, one is not. In one life he is a student, in the other he is on a ship headed to the Mariana Trench. Every part of reality has its own parallel in Caden’s imagination. His medications are cocktails, his roommates are his fellow seamen, his asylum is his ship. This design, the interchangeability of two stories that only one of which is true, that is what shows the horrors of schizophrenia. The despair that is illustrated through not only Caden’s story, but also Brendan’s input feels much more evident than Don Quixote. The book is a poignant account of a miserable journey and it’s use of non-linear chronology is certainly one of the best I’ve seen in a long time. The constant state of disorientation that Caden is in during his gradual descent into schizophrenia is extremely effective in conveying the surrealist, capricious reality that is schizophrenia.. While many of the metaphors in the book are not exactly subtle, they are still extremely effective. The Kraken and Charybdis represent Caden’s interpretation of his schizophrenia, the consuming nature of it, the endless downward spiral. The eternal battle between the giant squid and whale represent the warring aspects of his mind, his chaos and wisdom. His battles with schizophrenia are, of course, defined by is journey to the deepest point of the sea, and rise, followed by a warning of the inevitable repetition of this cycle. Overall, Challenger Deep is a nuanced and complex portrayal of perhaps the most nuanced and complex mental illness.

Fiction was never supposed to be purely entertainment. It teaches you what reality cannot. Works like "The Wasp Factory," "The Mask of Sanity," and "Challenger Deep" show you what you cannot imagine, allowing you to actually understand the insane. They do the impossible, they teach you the incomprehensible. And that is why, they are, and will be remembered as the greats of fiction.