The Hitchhiker's guide approaches the topic of meaning via the main plot line of its first installment of the same name. A brief synopsis of the events are as follows. A hyper-intelligent race constructs a computer to find the great Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything. After 7.5 million years, 42 is the answer given. Unfortunately, the meaning behind this answer is misconstrued in popular culture. People tend to find the fault with the question rather than the answer. They take the lesson to be that answers are useless without their initial questions. To be fair, even the book follows this logic, by immediately starting on the construction of a new supercomputer to find the Question. This is perhaps, another casualty of Adams’ penchant for mixing humour with philosophy, often to the point where they are impossible to differentiate. 42 is humorous, but it also means something much more. My interpretation of the Answer is based on events that take place in later installment, perhaps Adams’ more gradual way of guiding the reader to his fundamental truth. Firstly, we must establish that the Answer is just a placeholder of the Meaning (with a capital M) of life. Secondly, we must establish that Adams’ assorted quotes and tangential stories littered around the books are just as important as the main plot lines in this matter. It is from these tangents and other assorted quotes that Adams’ shows us his philosophy on Meaning.

I will be initially focusing on a tangential story which is told by a side character called Prak, who overdoses on truth serum. On his deathbed, he tells a story of a past life where he was a messenger for the Dwellers of the Forest. Two nearby tribes, the Princes of the Plains and the Tribesmen of the Cold Hillsides, were constantly at war in the territories of the innocent Dwellers, killing Dwellers and enemies indiscriminately. Prak was sent to the leaders of the warring tribes to find out why they fought in the Forest and killed the Dwellers rather than settling their conflicts elsewhere. Prak is given a reason, an amazing, convincing reason and he accepts it and starts on his way home. As he returns, the reason slips from his mind like snow melting in the sun. All he remembers is that there was a reason, and it was an amazing reason, and he was content with that. This reason is not too unlike the Answer and the Answer is not too unlike Meaning with a capital M. Introduced here is the concept of content with the knowledge that something exists rather than knowing exactly what it is. Prak may have forgotten the reason, but he did remember that it was there, and it was beautiful and that was enough. Well, enough to convince him to do nothing more and watch his tribesmen be slaughtered again. Perhaps he was foolish, perhaps the reason was just that amazing. Or perhaps it doesn’t matter either way since the continued slaughter was guaranteed no matter what Prak did. I see that as an amazing metaphor for meaning. Meaning exists quite irrespectively of your inclination to believe as such. On the grand scale of fate, your understanding of your meaning is meaningless.

I have had my fair share of assorted trinkets that I have destroyed in my pursuit to understand. Even Adams’ mentions how Arthur’s daughter breaks his watch while trying to understand it. People tend to fear things they do not understand. The urge for knowledge is a very human thing. Knowledge is power after all. If I know something, I can control something. I will know what there is to fear and what there is to love. An essential tenet to self-preservation and enjoyment. There is still some fear and love for things we do not understand though, and it truly is a tragedy when our search for truth wrecks the very things we seek to understand. It is a risk we take too often at times. We meet our heroes to be disappointed. We learn our history to be disgusted. We see the world to be horrified. Sometimes, the truth isn't what it was promised to be. Many amazing things tend to have disturbing details. Ever seen the first picture of Earth taken from space. How inspiring! Too bad the camera was launched on a Nazi weapon. The picture is still amazing, but perhaps the quest for more knowledge might have ruined the admiration that a random person might feel for this event. I’m not saying that Meaning is probably disappointing. I’m saying some things can be admired from a distance. Getting closer simply affirms your admiration or reverses it. An unnecessary risk, a meaningless risk. “Isn't it enough to see that a garden is beautiful without having to believe that there are fairies at the bottom of it too?”. The very effort of exploration is what sets expectations, affirming the inevitability of despondency.

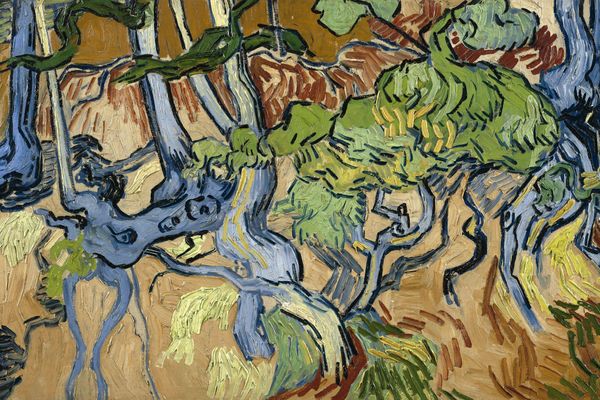

In the Guide, an often-repeated message is Don’t Try and let things happen. Trying to fly is useless. Rather, the knack to flying lies in learning how to throw yourself at the ground and missing. Almost all the danger in the book is resolved by chance and by no effort by the main characters themselves. The Question was accessible at several points in the book, Arthur mentions he must have “learnt it along the way”, Marvin knows the Question but is never asked, etc. Ironically, the efforts made to understand the Question were the least effective in understanding it. This philosophy is gone into greater detail by an author named Mark Manson in The Subtle Art of not Giving a “ ”. I encourage you to read the first chapter which touches on this subject. Also to be noted is that among the descriptions of the Universe, many blame pure chance for significant events that happen. Minuscule probabilities brought to reality by sheer scale. Adams’ seems to like the notion of chance, mere probabilities shaping your life. He seems to say that there is no Great Truth that explains everything. What you experience is what happens. Enjoy the ride. Don't Try, don't look for things that don't exist. Want to know how the ride works? Just look down at the incessantly turning wheels. There isn't much more to it. The mystery of life isn’t a problem to solve, but a reality to experience. Meaning is begotten by its absence in your efforts to understand it.

I suppose another order of business would be to actually explore the Question. Several ridiculous theories have come up, suggesting some obscure, nonsensical meaning behind 42. The significance of 42 in base 13, ASCII, binary code; all preposterous. There are even theories looking at the significance of 42 in Christianity and Buddhism (Adams’ was a self-described ‘radical atheist’). 42 is simply a number, and nothing more. But the Question is quite interesting. The Answer being 42 connotes that the question is quantitative, which any self-respecting philosopher would probably disagree with. Nevertheless, I believe that the question was revealed in the book itself. There are a number of clues that tell us this. An often-overlooked character is Marvin the Paranoid Android, but some things about him are rather crucial to the story. In a rather insignificant piece of dialogue, he casually describes himself as having a brain “the size of a planet”. A very similar description to the computer constructed to find the question. He even explicitly states that he knows the question but is not believed by the other characters. Marvin does ask an interesting quantitative question to a mattress at one point. He asks, “Think of a number, any number”. The mattress responds, “Er, Five”. Martin says, “wrong, you see?”. I think that that was the Question. Meaningless. A reiteration of the belief that should the main characters have found the Question; they would have been sorely disappointed. This game of numbers is quite interesting though. In a separate instance, Arthur finally attempts to discover the Answer via chance, by pulling random numbers out of a bag, blindfolded. Interestingly, he still does not get 42. I believe that this tells us the Answer is not 42, or at least not only 42. "Think of a number?". No. "Think of a meaning". There are multiple Answers, multiple Meanings. On hindsight, this makes sense, why would everyone have the same meaning? Meaning is what you make it, the pursuit of meaning is meaningless, meaning is something you don’t know that you already know.

I suppose the greatest proof of this is the book itself. The book feels deeply philosophical to read, but I do encourage you to read it and try to understand what it means on your own. You will likely be confused trying to understand how a book that seems to be a random collection of extraneous escapades can still feel as if there is some great meaning behind it. Perhaps this was Adams’ final clue.